Note: If you haven’t read part 1 or part 2, please do so! This post will be building off the previous material, and I promise they’re at least semi-entertaining/useful.

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Lists

- Iterators and Looping

- List like objects.

- Conclusion

Introduction

Hello again! In part 1, we gave a bird’s eye overview of the differences of Python and Java, which included lists. In part 2, I talked about functions, and included some stuff about lists, including why updating one inside of a function changes it outside the function as well. At this point, you may think you know all there is to know about lists. And you do know a lot of it already! But lists are one of the most important data structures in Python, so it’s worth spending a lot of time fully understanding them.

Data is one of the most important parts of programming - once you have the data you need, you need to somehow store it. Lists are by far the most common way to store data in Python, so it’s worth it for you to take your time in understanding how they work and how to properly use them. Topics we will cover include list basics, how to slice and index lists, methods on lists, functions related to lists, how to create lists from other lists without loops (list comprehensions), and how lists are similar to strings and tuples.

We’ll be talking about loops too, how they’re similar to Java loops, how they’re different from Java loops, and how you can use Python features to avoid all the nasty bugs you come across when using loops.

Note: This blog is full of interactive embeds from repl.it and pythontutor.org. If you see large blank spaces, please refresh the page and don’t switch tabs until it’s fully loaded.

Lists

Basics

As a quick reminder, lists are the Python’s most common object for data collection. They are similar to the ArrayList in Java, where they don’t have a specified length, but the syntax for dealing with them is much nicer. There isn’t anything like the Java Array built into Python, since lists are good enough most of the time (though they do exist in the library NumPy). Python lists are even more accepting than ArrayLists, as they can be of any type, and objects of multiple types can be in a list, including lists and dictionaries.

nums = [1, 3, 5]

crazy_list = [True, 1.0, 4, "test", [1, 2, 3], {'a': 'b'}]Lists are ordered, meaning that the order you insert items into a list matters, and the list’s items can be accessed in a specific predefined order. To access an element of a list, you use the same indexing syntax as Java arrays.

nums = [1, 3, 5]

print(nums[1]) # 3Python includes a useful extension of this, where you can also index starting from the back with negative indexing. The last item is index -1, the second to last item is index -2, etc…

nums = [1, 3, 5]

print(nums[-2]) # Also 3So you can access each element two different ways. Here’s a visualization of the regular and negative indexing:

# Regular: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

# Negative: -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1

full_list = [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13]So you can get the last item with nums[-1]. So much nicer than nums[nums.length-1], right!?

Just like Java, you can use indexes to modify certain parts of the list.

nums = [1, 3, 5]

nums[0] = 100

print(nums) # [100, 3, 5]Slices

Python also lets you grab a “slice” of a list, meaning a specific part. Here is the most basic way to do that:

nums[start:stop]

# example:

# 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

full_list = [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13]

print(full_list[1:5]) # [3, 5, 7, 9]This syntax will give you the elements of the list from start up until (not including) stop. So in this case, full_list[1:5] get back the list with the items at index 1, 2, 3, and 4, so [3, 5, 7, 9].

You can also use negative indexes in your list, so nums[1:-1] will give you everything starting at the item at index 1, up until the last element.

nums = [4, 5, 6, 7]

print(nums[1:-1]) # [5, 6]If you want to start at the beginning, or go until the end, you can also leave parts of the “slice” blank. Here are examples of those:

nums = [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

print(nums[:3]) # Start from the beginning until index 3. [10, 11, 12]

print(nums[3:]) # Start from index 3, go to the end. [13, 14, 15]

print(nums[:]) # Start from the beginning, go to the end (so the whole list.)That last one may seem useless, but it’s a common way to make a copy of a list, so don’t be too weirded out if you see one of those.

Finally, list slicing actually has a third optional parameter for a “skip”, which lets you skip every N element in a list. Here’s some examples:

nums = [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]

# Starts at 1, up to 7, and only every 2nd item.

# So indexes 1, 3, and 5.

print(nums[1:7:2])

# From the beginning to the end, every other number.

# So indexes 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10

print(nums[::2])

# Every element, but skipping backwards.

# This will reverse the list!

print(nums[::-1])Just as a note: the slices you get back are copies of the original list, so if you modify them, you won’t modify the original list. However, if you don’t set them to a variable, you can also use slices to redefine whole parts of lists as other lists! Pretty sweet :)

>>> nums = [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]

>>> nums[1:8]=[0] # Replace items from 1-8 with just a 0

>>> nums

[10, 0, 18, 19, 20]Here’s an interactive REPL you can play with.

I suggest clicking the “debugger” button on the left so you can go through it line by line and see what is going on. Watch the CEO of repl.it do it here:

We've recently made it possible to step through programs in embedded @replit.

— Amjad Masad (@amasad) September 17, 2018

This is from the excellent "Python for Java Programmers" by @misingnoglic pic.twitter.com/FMRF47G21W

And there you have it, Python slices!

Methods on lists.

Python lists have a few methods which are fairly useful. Note that any of these that change the list will also affect any variables that point to the same list. I’ll list them below:

append(x)

nums.append(x) will add the item x to the end of nums.

nums = [1, 2, 3]

nums2 = nums

nums.append(5)

print(nums) # [1, 2, 3, 5]

print(nums2) # Also [1, 2, 3, 5]clear()

nums.clear() will clear nums of all its items.

nums = [1, 2, 3]

nums.clear()

print(nums) # []copy()

nums.copy() will return a copy of nums, so that any changes you make to the copy won’t affect the original. This is one of the unique methods that will return a new object.

nums = [1, 2, 3]

nums_new = nums.copy()

nums.append(5)

print(nums_new) # [1, 2, 3]Remember that this can also be done with nums[:].

count(x)

nums.count(x) will return the number of times x is in nums.

# X X X X

nums = [1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 3]

print(nums.count(1)) # 4extend(new)

nums.extend(new_list) will add all of the elements from new_list into nums. Here’s an example:

nums = [1, 2, 3]

new = [4, 5, 6]

nums.extend(new)

print(nums) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]index(item)

nums.index(item) will return the first index of item inside of nums.

nums = [1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3]

print(nums.index(2)) # 1If the item isn’t inside of nums, the program will raise a ValueError. I’ll quickly show you how you can write code to catch one of these, so you can use the .index() method without worrying that it will crash your whole program.

nums = [1, 2, 3]

try:

print(nums.index(4))

except ValueError:

print("4 is not in nums")I’ll probably talk a bit more about exceptions later, but that’s the gist of it! You can also use the in operator to check if an item is in the list safely (in is discussed later in the post).

insert(index, item)

nums.insert(index, item) will insert item into the index before index. Some examples:

nums = [1, 2, 3]

nums.insert(0, 100) # Insert 100 at the beginning.

print(nums) # [100, 1, 2, 3]

nums.insert(2, 200) # Insert 200 before index 2.

print(nums) # [100, 1, 200, 2, 3]

nums.insert(-1, 300) # Insert 300 before index -1 (second to last item).

print(nums) # [100, 1, 200, 2, 300, 3]You might be thinking - but what if you want to add the item to the end? Well, just use append!

pop(x=0)

pop() is an interesting method - it returns the last item of a list, but also removes it from the list. You can also pass it an index, and it will instead pop that index.

nums = [1, 2, 3, 4]

x = nums.pop() # 4

print(nums) # [1, 2, 3]

y = nums.pop(0) # 1

print(nums) # [2, 3]If you’re an advanced reader, pop allows you to use a Python list like a stack or queue. If you don’t know what those are, and don’t mind a depressing example in capitalism: imagine you’re a manager at a company whose policy for layoffs is “the last person to join will be the first person fired.” You could have a Python program like this:

employees = []

def hire_employee(employees, employee):

employees.append(employee)

print(employee+" was hired.")

def fire_employee(employees):

fired_employee = employees.pop()

print(fired_employee+" was fired.")

print("Leftover employees: ")

print(employees) # All but the last itemYou can play with it here - try to match the print statements to the calls to pop and append.

Now imagine you had a list of people you wanted to hire, but didn’t have room for. You have now a list of potential_employees, and whenever you have room to hire someone, you want to hire the person who’s been waiting the longest. You could do potential_employees.pop(0) to remove them from the front of potential_employees, and then add them to employees! That’s a much better example! If you use a list in the Last In First Out (LIFO) model, it’s called a Stack, and the list is used in the First in First Out (FIFO) model, it’s called a Queue. These are good CS words to know, if you aren’t already familiar. If you’re studying for software interviews, correct usage of pop() will be extremely helpful in certain problems!

If this pop section didn’t make much sense to you, don’t worry! Just know that you can use pop on a list to remove an item from a specific index. That’s it!

remove(item)

nums.remove(item) will remove the first instance of item from nums. This is fairly self explanatory.

nums = [1, 2, 3]

nums.remove(2)

print(nums) # [1, 3]sort()

nums.sort() will sort nums in place. This is different from the sorted function I talked about in part 2, since sorted returns a new list while sort just modifies the list it was called on. With no parameters, sort will just sort the list from smallest to largest.

nums = [8, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3]

nums.sort()

print(nums) # [1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8]sort can take an optional argument reverse, that when set True will sort the list from largest to smallest.

nums = [8, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3]

nums.sort(reverse=True)

print(nums) # [8, 5, 6, 7, 1, 2, 3]sort can also take another optional argument, key, which is a function that you sort the list based on. For example, if you have some weird ranking where even numbers are worth 100 more than if they were odd, you could sort your list like this:

nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 191]

def sort_fn(x):

# Add 100 to evens

if x%2==0:

return x+100

else:

return x

nums.sort(key=sort_fn)

print(nums) # [1, 3, 5, 2, 4, 6, 191]This basically sorts the list as if every element x of nums is sort_fn(x), but keeps each element the same. Another example: let’s say you have a list of students, but you want to sort it by the last letter in the name to change things up a little. You could do something like this:

names = ["Billy", "Parisa", "Sam"]

def sort_fn(name):

# return last letter

return name[-1]

names.sort(key=sort_fn)

# Sorts the list by the last letter.

print(names) # ['Parisa', 'Sam', 'Billy']Finally, let’s say you have a list of lists (#inception), and you want to sort them by their sum. You could just pass in the built-in function sum which returns the sum of a list.

test_scores = [[200, 300, 0], [90, 80, 75], [100, 150, 0]]

test_scores.sort(key=sum) # Sort by sum function

print(test_scores) # [[90, 80, 75], [100, 150, 0], [200, 300, 0]]sort is a great method for dealing with data, as it lets you have it ordered in a predictable way. In case you were wondering what Python’s sorting algorithm is, it’s not one you learn about normally in classes. It’s called timsort, and it’s named after Tim Peters, one of the earliest developers of Python itself. I hope one day I have an algorithm named after myself.

Built In Functions for Lists

Besides the methods on lists, there are a lot of built in Python functions that are related to lists. I’ve already mentioned a lot of them, but I’ll put them here for posterity’s sake.

in

in isn’t actually a function, it’s a keyword (like and or if), but this was the best section for it. You can use it to tell if an item is in a list, with surprisingly readable syntax.

nums = [5, 7, 9, 11]

if 9 in nums:

print("nums has a 9!")

else:

print("no 9 in nums...")x in nums will return a boolean that describes whether the variable x is in nums or not. This is one of my favorite python things to show new programmers, since it’s amazing how readable this syntax is once you get used to it.

not in

not in is the super readable cousin of in. You can use it to test if an element is not in a list.

nums = [5, 7, 9, 11]

if 5 not in nums:

print("There's no 5 in this list")Functionally it’s the same as doing if not x in nums, but if x not in nums reads better, so use that instead.

range(stop)

range() is definitely one of the most important list functions, as it can create lists of numbers in a certain range, meaning you don’t have to write the loops to do it. range() is a function that returns an “range object”, which is kind of like a list that isn’t evaluated until you actually need the item you’re asking from it. It basically works the same as a list in terms of indexing and looping. This type of object is called an iterable, meaning it can be iterated over.

range(stop) will return an iterable from 0 up until the stop number. Just like list indexing, you can also give it a start, and a skip. For visuals I’ll convert them to lists, but when you use them you mostly won’t have to:

>>> list(range(5))

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> list(range(1, 5))

[1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> list(range(20, 100, 5))

[20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 65, 70, 75, 80, 85, 90, 95]

>>> list(range(10,0,-1))

[10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1]If you give range() one parameter, it will return the range object from 0 until the parameter (not including the parameter). If you give it two parameters, it will return an object starting from the first parameter up to the second parameter. If you give it three parameters, it will use the third one as a skip, so it will skip by that number for each entry. So range(1, 5) will give the numbers [1, 2, 3, 4], and range(20, 100, 5) will give all the numbers from 20 up to 100, skipping by 5 every time.

If you don’t convert it into a list, a range object will just show you this:

>>> x = range(100)

>>> print(x)

range(0, 100)So it hasn’t actually computed anything. So why did the creators of Python decide to make range lazy? Let’s say you wanted to do something for every number from 0 to a billion. If range() wasn’t lazy, it would have to store each item from 0 to a billion in a list somewhere in memory, which would be highly inefficient. It’s much easier to just not get the number until you need it, and then convert it into a list if you really need it as a list. So if anyone ever tells you being lazy is bad, tell them that sometimes it’s the best policy :)

(Note, in the 2.x version of Python, range() returned a list, and you needed to use xrange() to return a range object).

reversed(nums)

Sort of like range, reversed takes in a list, and returns an iterator with the reverse of a list. an iterator is another kind of lazy object that you can loop over. I’ll talk more about looping at the end of this post, but here’s an example:

nums = [1, 2, 3]

for i in reversed(nums):

print(i) # 3, 2, 1 If you want to just get a reversed list, remember you can always just do nums[::-1]

sorted()

The sorted() function is exactly like the .sort() method on lists, except that it returns a new list. It can also take the optional parameters reversed and key.

nums = [1, -3, 2, 5]

new_nums = sorted(nums)

print(new_nums) # -3, 1, 2, 5

print(sorted(nums, reverse=True)) # 5, 2, 1, -3

# abs is the built in absolute value function

print(sorted(nums, key=abs)) # 1, 2, -3, 5len()

len(nums) will just return the length of the list.

nums = [1, -3, 2, 5]

print(len(nums)) # 4max()

max(nums) will return the largest element of the list. Just like sorted, it can take a key function as a parameter to determine the maximum however you like. For example, you can pass abs (the absolute value function) if you want the number with the largest absolute value.

nums = [1, -7, 2, 5]

print(max(nums)) # 5

print(max(nums, key=abs)) # -7min()

min(nums) is the mirror of max(), where it will return the smallest element of the list. It can also take a key parameter.

sum()

sum(nums) will return the sum of the list. Fairly straightforward.

And with all that, you have the built-in tools to use lists! Most calculations you need to do on lists can be done with these functions, for example:

def average(nums):

return sum(nums)/len(nums)

def range(nums):

return max(nums)-min(nums)There is one more feature of lists though that’s too awesome to not mention though, so hold on tight!

List Comprehensions

I’ll just say this: list comprehensions are amazing and beautiful. If you can master list comprehensions, you’ll be able to take something that took several lines of Java to build, and do it in a single line. They’re seriously quick, readable, and easy to start using once you get how they work. They have the added benefit of avoiding bugs as well! Ok - I think I’ve hyped them up enough - now what exactly do they do?

Mapping

List comprehensions let you create a new list out of an old list, without using any sort of loops. If you give the list comprehension some kind of function to map onto the list, you’ll get the new list. For example: let’s say we have a list of grades for a test, and we want to curve everyone up by 10 points. In Java, that would look something like this:

// let's say we already have our list of grades

int[] new_grades = new int[grades.length];

for (int i = 0; i<grades.length; i++){

grades[i]+=10;

}Ok, “not bad” you say. But take a look at this:

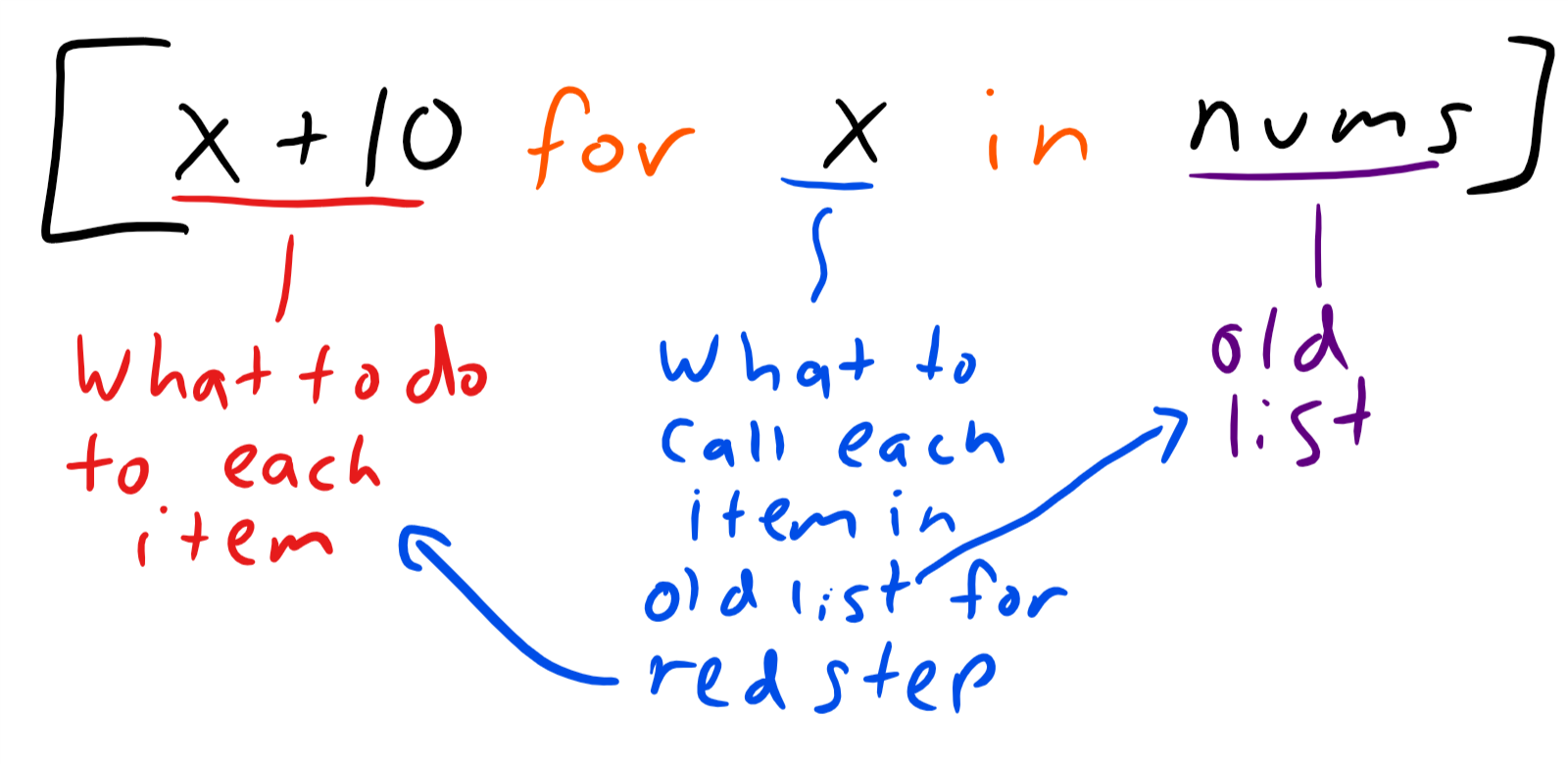

new_grades = [x+10 for x in grades]Ok, let’s break this down:

for x in grades is basically saying “for each thing in grades, call it x.” And x+10 is saying what to do to each of those x’s. So basically, this is saying “for each element in grades, add 10 to it.” Instead of writing the loop, you just say what you want to happen to each element, and it happens! No chance of an off by one error, or array out of bounds exception.

If you read the list comprehension as it looks, “x plus ten for x in grades,” I think it will start to make sense.

Example: You have a list of grades out of 100, and you want to turn it into a list of decimal grades:

new_grades = [x/100 for x in grades]You can also use the range() function in list comprehensions to create a new list from an iterator returned by range. For example, if you want all of the numbers from 1 to 100 squared, you can do:

squared = [x*2 for x in range(10)]Your expression doesn’t even have to involve x. For example, if you wanted a list of 100 zeroes, you could do something like this:

zeroes = [0 for x in range(100)]Notice how the function part doesn’t involve x, even though we called each item in the list x. You don’t need to use your variable in your list comprehension, if the returned list doesn’t need it. As another example, let’s get the last character in a list of strings.

names = ["Billy", "Parisa", "Sam"]

print([name[-1] for name in names]) # [y, a, m]Filtering

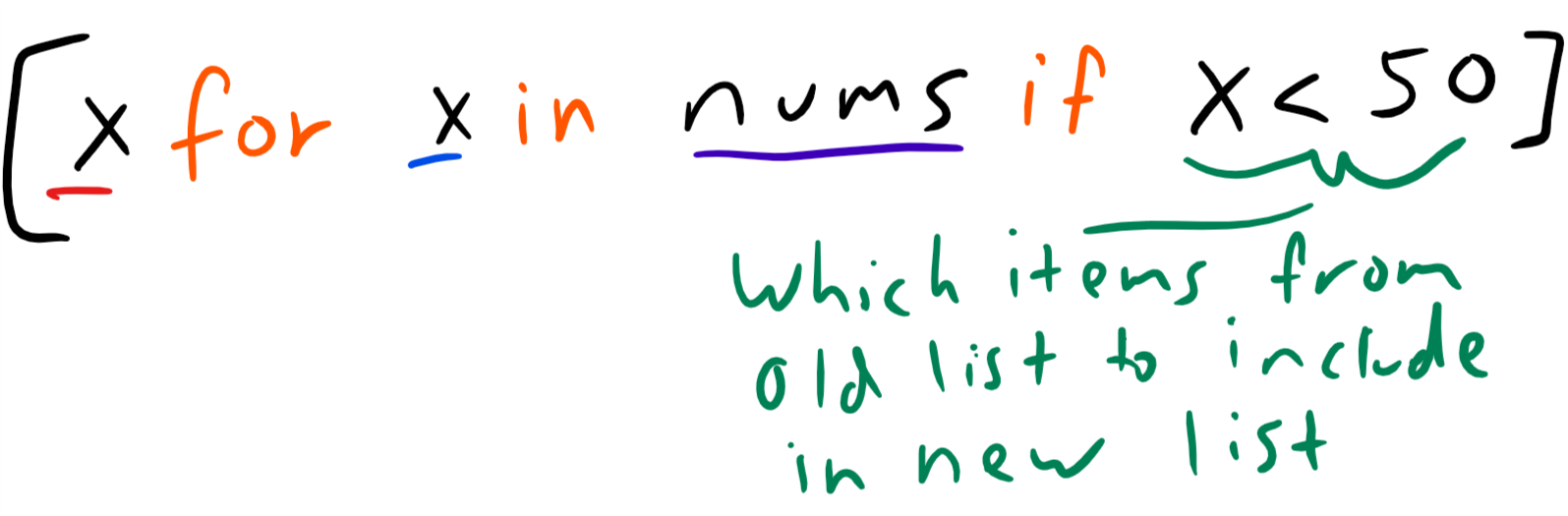

Lists comprehensions can also be used to filter lists based on some criteria. Here’s a toy example - if you have a list, and you want to get all of the even numbers from that list:

nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

even_nums = [x for x in nums if x%2==0]Or all of the numbers greater than 50:

big_nums = [x for x in nums if x>50]

To break this down:

x for x in numsjust means to return just x, not some modification of x. If it wasx+2 for x in nums, it would be adding 2 to each number.if x > 50will only put the numbers in the list if they are greater than 50. Note that the statement here should be some boolean statement that isTrueif you want to keep the item.

So the full form of the list comprehension is as follows (though the if part is optional):

new_list = [manipulation(item) for item in old_list if some_criteria(item)]Where manipulation(item) is some function that takes in item and returns something new, and some_criteria is some function that returns a boolean. You don’t need to create a new function - as you see from the above examples you can just put the expressions in directly, but you can also use functions for more complicated manipulations or filters.

A complex example - let’s get the squared value of all even numbers.

crazy_list = [x**2 for x in nums if x%2==0]You can also use range in a list comprehension with filtering. For example, if you had a function is_prime which returned True if a number is prime, you could do something like this to get all the primes from 1 to 1000:

primes = [x for x in range(1,1000) if is_prime(x)]Going through nested lists.

A lot of times while programming, you will be dealing with functions and APIs that return nested lists to you. List comprehensions allow you to navigate through those lists and return the data you want in the format you want it in. For example, let’s say you have a list of students, where each student is represented by a list of two items, their name and their grade in the class. So something like this:

students = [["Sam", 80], ["Carly", 90], ["Dmitri", 65], ["Parisa", 100]]If you want to get a list of all the students whose grades are under a 70, you can write a list comprehension like this:

failing_students = [student[0] for student in students if student[1]<70]Remember that students is a list of lists, so student in each case will be a list, where student[0] is the name and student[1] is the grade. To make this more clean, you can even do something like this:

failing_students = [name for name, grade in students if grade<70]Python lets you assign multiple variables in one line, kind of like this:

x, y = [1, 2]

print(x) # 1

print(y) # 2So by doing for name, grade in students, it’s taking each list of two items in students and assigning the first item to name and the second item to grade. This second version is more pythonic, since it’s more explicit and easier to read and know what’s going on.

In the end, list comprehensions are a great tool that you should really work to master, as they’ll eliminate many issues involving loops, and they’ll elevate your code to the next level. They’re also great for coding interviews!

Iterators and Looping

Now that you have lists, and I’ve taught you how to use them without loops, you may still be wondering “well how do I actually loop through the list though?” Sigh… some people never break out of their Java habits.

But seriously, before you write a loop, think “can I do this without a loop?” If the answer is yes, then do it without a loop. However, if your problem is not simple enough to do in a list comprehension, then you may well use a loop.

Python has two kinds of loops. The first one, the while loop, works exactly like the Java while loop, except you don’t need parentheses. You put a boolean statement next to the while keyword, and the loop will run until that is not true anymore. Here’s a simple example:

x = 0

while x<10:

print(x)

x += 1This loop has the same issue as Java’s, where if you’re not careful, your loop can potentially go on forever (e.g. if I forgot to add 1 to x every time). There’s not much more to say about this kind of loop. Note that there isn’t a do while loop in Python.

The second kind of loop is the for loop. This kind of loop acts like the for each loop in Java:

for (int num : nums){

System.out.println(num);

}The Python one is very similar. Here is the syntax:

for x in nums:

print(x)Super simple, and readable right? The for loop takes any iterable object (like a list, range, string, etc…) and loops over each item. Just like the list comprehension, if you have a list (or any iterator), you can assign each item to a variable name, and then do something for each item in the list. In the above case, it will print every item of nums.

It helps to read this straight on, so “for [each] x in nums, print x.”

You might wonder why there’s nothing like the regular for loop in Java, like this:

for (int i = 0; i<10; i++){

System.out.println(i);

}The reason is that you can mostly handle anything you need to do with these two kinds of loops, plus list comprehensions. If you want to loop through all the numbers from 0 to 10, you can do something like this:

for i in range(10):

print(i) # prints 1-10Or if you really need the indexes of items in the list, you can do something like this:

nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

for i in range(len(nums)):

if i>0:

# Print each item plus the number before it.

print(nums[i]+nums[i-1])range(len(list_name)) is a good pattern to remember for looping through each index of a list. Remember, since range() returns an iterable, you do not need to convert it back to a list.

If you need both the index and the item, you can use the enumerate function, which gives you both in a more readable format. Here’s an example:

def index_of_first_even(nums):

for index, num in enumerate(nums):

if num%2==0: return index

return -1 # Not found

x = index_of_first_even([1, 3, 6, 4]) # returns 2If you want to loop over two lists of equal length at the same time, instead of using the indexes, you can use the zip function, which zips two lists together.

# Using indexes

nums1 = [1, 2, 3]

nums2 = [10, 20, 30]

for i in range(len(nums1))

print(nums1[i]+nums2[i])# Using zip (more readable)

nums1 = [1, 2, 3]

nums2 = [10, 20, 30]

for n1, n2 in zip(nums1, nums2):

print(n1+n2)Or even as a list comprehension, to store the new list:

nums1 = [1, 2, 3]

nums2 = [10, 20, 30]

sums = [n1+n2 for n1, n2 in zip(nums1, nums2)]Python really tries hard to give you the tools to loop through a list without having to use the indexes, to avoid messy code and hard to catch errors. Sometimes they’re necessary, but make sure they are before looping through range(len(nums)).

In the end, if you wanted to make a list out of an old list, you could do something like this:

nums = [1, 3, 3, 4, 5]

new_nums = []

# each i from 0 to length of nums

for i in range(len(nums)):

new_nums.append(nums[i]*10)But isn’t it much nicer to write the equivalent:

nums = [1, 3, 3, 4, 5]

new_nums = [x*10 for x in nums]You can even combine list comprehensions with functions like sum and max to avoid these loops. Before writing a loop, make sure you can’t do the same thing with range and a list comprehension. And when writing a loop, avoid using indexes if at all possible!

List like objects.

To conclude this post, there are a few objects that behave very similarly to lists, and are worth going through here.

Tuples

The first similar object is the tuple. The tuple is like a list, but it is immutable, meaning its contents cannot be changed or added to once it’s created. In practice, this means that you cannot append to it, and you cannot change its items at any index. You define it with parentheses. For example, if you wanted to represent a point on an x, y plane, you could do so with tuples, where the first item is the x coordinate, and the second item is the y coordinate.

point = (3, 2)Actually, you don’t even need the parentheses. This is equivalent:

point = 3, 2This is also useful in functions when you want to return two things.

def complex_function():

...

return answer1, answer2This will return a tuple of (answer1, answer2). Generally you want your functions to just do one thing, but there are times that it’s nicer to return two things (for example if you’re doing some intense computation that you don’t want to redo).

Tuples support the same slicing as Python lists, and can be passed into a for loop as well. Use them like you would any other variables, but when that idea needs to contain multiple parts (kind of like an object without methods). You can also always convert a list to a tuple using the tuple, or a tuple to a list using the list function.

t = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

print(len(t)) # 5

print(t[0]) # 1

print(t[-1]) # 5

print(t[1:-1]) # (2, 3, 4)

print(t.count(2)) # 1 (1 instance of 2)

for x in t:

print(x)

print(list(t)) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(6 in t) # False

t[0] = 5 # TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentTuples are great when you want to state that the data you’re returning is not to be modified or appended to, and should be treated as a constant value, such as a tuple that represents a point in space.

Strings

The other type of object in Python that’s similar to a list is a String, which I won’t describe in too much detail. This makes sense from a design standpoint, since what are strings but just an object that contains a list of single characters! But in Java, Arrays and Strings have completely different methods on them! You have to remember that arrays use .length, strings use .length(), and Lists use .size(). Additionally, for Java Strings, you have to use .charAt() to get the character at a certain index, or .substring() to get a substring. With Python, it’s the same syntax as a list! You index the same way, slice the same way, even compare them in the same way with ==. This is great, since it means you only have to learn one syntax! The only difference is like the tuple, strings are immutable (just like Java).

>>> s = "Hello World"

>>> "Hello" in s

True

>>> s[:5]

'Hello'

>>> s.lower()=="hello world"

True

>>> for letter in s[:5]: print(letter)

H

e

l

l

o

>>> s.count("o")

2Note that strings can be single quotes, or double quotes. Multiline strings can be three single quotes or three double quotes as well, you just have to be consistent. Note that multiline comments and docstrings are just regular strings.

>>> s = '''

This is a very

long and large string

'''

def sq1(x):

'''

This function takes in a number and returns

its squared value plus 1.

'''

return x**2 + 1String Methods

Strings also have their own methods that are useful for string manipulation, like .upper() and .lower(). You can see the full list of those here. Here are some fun examples, whose results are fairly self explanatory. Note that they don’t modify the string (as the string is immutable), but they instead return a new string.

>>> s = "Hello world"

>>> s.upper()

'HELLO WORLD'

>>> s.lower()

'hello world'

>>> s.swapcase()

'hELLO WORLD'

>>> s.replace('o', '0')

'Hell0 w0rld'

>>> s.startswith('Hell')

True

>>> s.title()

'Hello World'These string methods are great for dealing with user input, or just formatting strings in a way that makes them nicer to look at.

Probably the most useful string function that I know of is split, which splits a string into a list, based on whatever separator you give it. If you don’t give split a parameter, it just splits on the space. The split method allows you to iterate through a string, searching for certain words or phrases.

>>> s = "This is a long sentence"

>>> s.split()

['This', 'is', 'a', 'long', 'sentence']

# You can also split on characters besides a space

>>> s.split("s")

['Thi', ' i', ' a long ', 'entence']

# Sort the words based on length

>>> sorted(s.split(), key=len)

['a', 'is', 'This', 'long', 'sentence']

>>for word in s.split():

>> print(word.swapcase())

tHIS

IS

A

LONG

SENTENCERemember that the return value of the input function is a string. You can combine split with list comprehensions to get all kinds of input though!

input_str = input("Enter several numbers, separated by spaces: ")

nums = [int(x) for x in input_str.split()]Think about how annoying that would be with the Java scanner!

Joining a List Into a String

Splitting a string into a list is fairly intuitive, but turning a list back into a string isn’t, so I’ll show you the preferred method for that. If you want to turn ["Hello", "World"] into "Hello World", you have to do something like this.

words = ["Hello", "World"]

combined = " ".join(words)

print(combined) # "Hello World"Basically, you’re taking the space string, and joining every word in the list based on it. I know it seems like it would make more sense to have the join method on the list instead of the string, but that’s just the way it is. Here is the real reason, in case you are curious. Note that this is more space efficient than writing a loop to create a string, so interviewers love to see stuff like this. I know it’s a strange syntax at first, but you will get used to it.

Adding Variables to Strings

A common thing to want to do with Python is add variables to strings, so you can create some complex strings. I’ll show you four ways to do this, from the best to the worst.

The easiest way to do this is with f strings, a fairly new feature introduced to Python.

num = 4

s = f"{num} squared is {num**2}"

print(s) # 4 squared is 16Simply just put an f in front of the string (to signify that it’s a format string), and then place your variables into the curly braces. Python will automatically format the string for you. This is amazing, but unfortunately this is only supported in Python 3.6 or above, so people with older versions of Python won’t be able to run it.

Another common way is by manually calling the format function like this:

num = 4

s = "{} squared is {}".format(num, num**2)

print(s) # 4 squared is 16Basically you just put {} wherever you want to place your variable, and then call .format on the string, placing each variable in order. Definitely not as nice, but you’ll see this a lot when writing Python.

You can also use the printf formatting that’s common with other programming languages like this:

num = 4

s = "%d squared is %f" % num, num**2

print(s) # 4 squared is 16This is definitely not as nice, so I won’t waste too much time explaining them. You can read about this kind of formatting here.

Finally, the clunkiest way you can do it is just by converting your variables to strings and adding them together.

num = 4

s = str(num)+" squared is "+str(num**2)

print(s) # 4 squared is 16Strings are super useful, especially for reading files and user input, and Python makes them so pleasant to work with! I’ll talk more about files, but this post is getting pretty long already!

Conclusion

I know this was a LOT to take in, but I promise it all gets easier with practice. You definitely don’t need to memorize all of this information about lists, tuples, strings, and loops, but as you program more and more in Python, it will all become second nature.

I hope this deep dive into lists was helpful, and has allowed you to more appreciate the wonderful syntax Python gives when dealing with data. In the next part, I’ll talk about other kinds of objects used to store data, and some of their tradeoffs. Please sign up for my mailing list to be notified when I post the next part. Additionally, please leave a comment and share with your friends if you found this useful.

Just FYI, my next post will be on using Python to create dynamic websites, and it’s almost done, so stay tuned.

Thank you everyone!